Inventing The Photographic Artist

(an old essay on the beginning of it all)

Origin myths endure as the keys to our identity. No matter what we use to define oursleves we must simply ask, How did this begin? When did this set itself apart from not this? It is no different for art, and we may imagine an artist’s essential nature by imagining that first creative act. However, we’d be looking too far back in time, with every artist aspiring to reach the purity of the primitive moment under the weight of an immense cumulative history. And yet, while identifying the First Artist would be an almost impossible task, for Photography there is a much more recent birthdate.

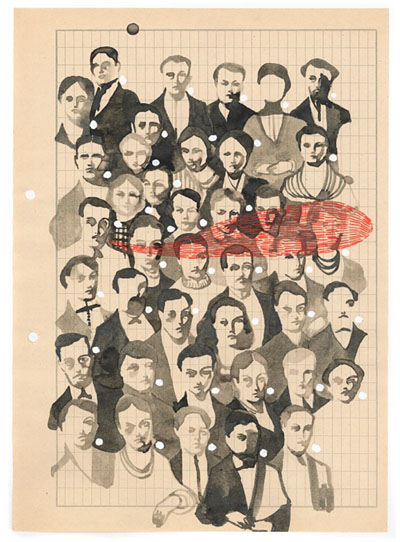

The origins of Photography offer fascinating stories, and its beginnings set the tone for all Photographic Artists to come. The two men generally credited as the originators may have as much myth as fact surrounding their respective inventions, but despite the wealth of information to be found about each of them, it is perhaps the myth that is more important. These historical archetypes might have shared much in common with our contemporary selves, and it is no stretch to imagine them feeling just as we do about their burgeoning art, over 150 years ago. We can almost conjure them before us through the stories about them, even more than through their first photographs. Much of the history we carry is oral history anyway, not necessarily the original facts. Rumors and stories are the only way we remember our birth.

And what do I remember of the first photographers?

First in most histories is Daguerre, the businessman and entrepreneur, successful in being the first to officially announce his process. He was successful, too, in getting the first state patronage for his art, enough to set him up for the rest of his life. (Is the First Artist the first Financially Successful Artist?) The story goes that the mercury from a broken thermometer, accidentally left in the cupboard with his silvered plates, allowed the developing breakthrough he needed to perfect the Daguerreotype (as if the Hand of God led him to the discovery!) I imagine it only helps his lasting mythology that all his working notes were lost in a studio fire – we know little of his failures, only his perfect process, born complete.

Second perhaps is Talbot, the polymath – a man of science, leisure and wealth. He has the great distinction of having created the first photographs on paper, the first “positive” and “negative” – terms coined by his good friend Sir John Herschel, who also gave us the first use of the word “photography” in reference to Talbot’s work. With the abundance of notes and letters Talbot left behind, we have a complete narrative from a witness at the birth of the Art. We have his “first original idea” to fix the images in a camera. We have a record of his chemical trials and errors. Maybe more importantly, we also have written down his struggles and missteps, a template for the methods of a working artist.

Third and last place must be reserved for any of a group of early would-be photographers. What about Hippolyte Bayard, the romantic failure, who had developed a process similar to Talbot’s, years before 1839? He was perhaps the first Poor Starving Artist, ignored by the state and its early official history. What about poor Nicephore Niepce, Daguerre’s precursor and partner, but dead before the accepted birthdate of the art, his work like children orphaned and adopted by others? What of Elizabeth Fulhame, one of the first to write a how-to on printing photographically, in silver on white leather…? And what about all the rest (and there were many others)? They are the ancestors of the unknown and unappreciated artists, working in solitude and obscurity. Even these acknowledged first points of origin are in question, since there were who knows how many “First Photographers” in other parts of the civilized world.*

Indeed there may be no one origin for Photography, despite its having an official history. While it may be the privilege of the inventors to define the history as written, it is our privilege now to misrepresent that history for our own interests. Even the recent past becomes willfully distilled in our memory. In turn, our license to misremember the past creates for us a somewhat fluid identity, but rooted in these few known facts about our ancestors. It’s as if we had several parents each with a few distinct traits to inherit, and we may pick and choose among them. It is not an unlimited choice, perhaps, but we may be any or all of these things: Outsider or Insider, Star or Failure, Genius or Gentleman (and Gentlewoman!)

So what are we left with? What, then, is the Photographic Artist, and why is he or she different from any other artist? The distinction persists in the art world even now. Perhaps other artists are freer to separate themselves from an origin myth born so long ago, while we Photographers still take after our young parents. Unmoored from their beginnings, they may be better able to see themselves as originators and inventors – such a prized commodity for any artist today. For now, Photographers come predefined by a relatively recent history.

Our Mothers and Fathers are known by name and reputation. We may have inherited Daguerre’s business-sense or his divine inspiration; Talbot’s wonder at Nature or his methodical obstinacy; or merely Bayard’s self-importance; yet we remain defined by them. Too connected to culture, science and light, all Photographers are tethered to the world. Although we may be slaves to the machine, the mirror and the tyranny of objects, still I will imagine my own First Photographer – the First Magician, the First Narcissist, the First Fetishist ….