One of the few true pleasures in life is the lift that comes with inspiration – that palpable leap of the insides that occurs at the very moment when an idea bubbles and pops within. It’s probably impossible to plan or to count on, but you sure can court the opportunity. Last month, I grabbed a fat book and took the long train ride from Brooklyn up to the Columbia Medical Library at 168th street, in search of just such a thing. The occasion was a lecture entitled Ink and Silver: Medicine, Photography, and the Printed Book, 1845-1880 by Dr. Stephen J. Greenberg of the National Library of Medicine. The lecture itself was small and rather dry, as it happens, covering the parallel and interlinked technological histories of photography and printing for books, much of which I already knew. I was glad to have come anyway. There were a lot of snacks, and plenty of wine, plus the unsurprising appearance of Dr. Stanley Burns of the Burns Archive (from whom I had borrowed some medical photographs for my show last year.) I think the basic idea of the evening was to show how photography changed the way medicine was depicted and sold in the 19th Century, and not just to the professionals of the time. However, there were a couple of little things mentioned that eventually clicked into place for me, and gave me new insight into my own work.

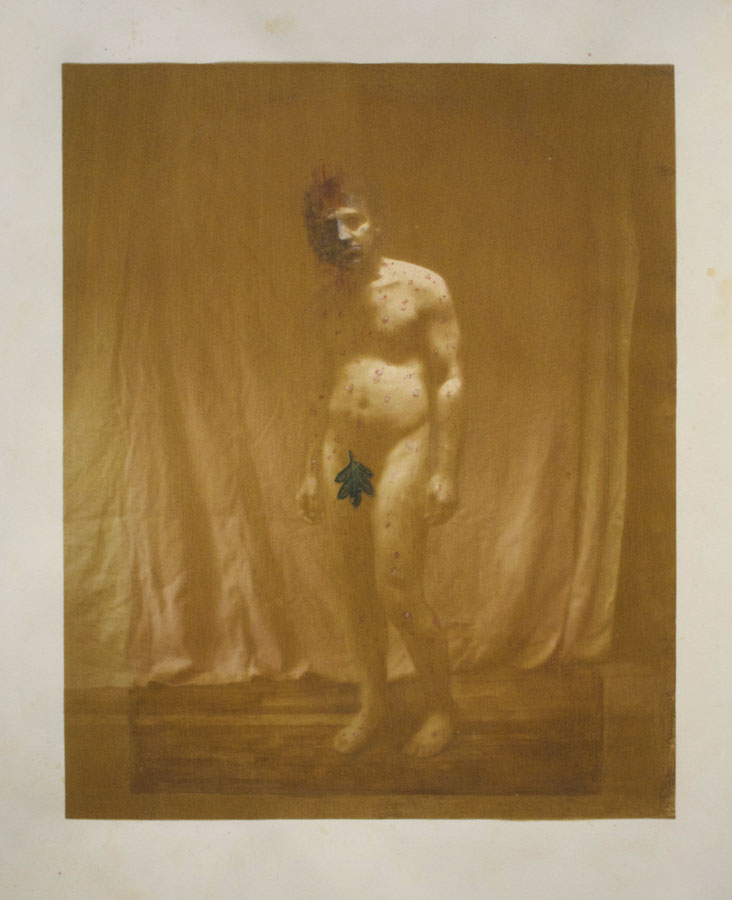

My photographs have often mimicked the look of these sorts of images – bodies shown as if on display for the camera, many bearing the signs and symptoms of (fake) diseases. I believe I just assimilated without criticism this blank and centered look, along with a range of other stylistic tics, from the artists that first inspired me: you can see it in Francis Bacon, in Joel-Peter Witkin, even a little in Meatyard and Arbus. I see it still in Saul Fletcher and Michael Borremaans, whom I follow today. These are images that pretend to be objective documents of a sort, however constructed, while containing the blunt acknowledgment of being seen and photographed. One is tempted to call this type of photograph a tableau, a term that became almost synonymous with the rise of the large constructed photographs of the 80’s, 90’s and beyond (Crewdson, Wall, et. al.)1 However, there is a distinction to be made between the images that seem to live in their own fabricated world without knowledge of the viewer (what Michael Fried calls “absorption”2) and those that demand the viewer’s participation, often as acknowledged voyeur. What to call this, exactly? “Display Aesthetics”? “Theatrical Objectivity”? And why does this tiny change in position – the inclusion versus the exclusion of the viewer – mean so much to me?

Here’s Adam Gopnik on Francis Bacon in the New Yorker (from February 26, 1990):

“A didactic white arrow is superimposed on the left-and right-hand panels, pointing almost sardonically at the dying man. (These arrows, Francis Bacon’s favorite distancing device, are sometimes explained as merely formal ways of preventing the viewer from reading the image too literally. In reality, they do just the opposite and insist that one treat the image as hyper-exemplary, as though it came from a medical textbook.) The grief in the painting is intensified by the coolness of its layout and the detachment of its gaze. It was Bacon’s insight that it is precisely such seeming detachment–the rhetoric of the documentary, the film strip, and the medical textbook–that has provided the elegiac language of the last forty years.” (emphasis mine)

What I realized from Dr. Greenberg’s lecture was that this language of presentation increases the strength of the photograph’s true power – what I like to call “Belief” (although I guess I mean “Verisimilitude”.) It is the Belief in the truth of a photograph – even when we know it is a lie or a fake – that makes it different from a drawing or painting. (Think of the difference in feeling from a photograph of a dead body versus a drawing of one.) By its assumed stance of objectivity, medical and scientific photography hews to the lie of Truth even more, thereby increasing our innate attachment to the image. In addition, our empathy with the person depicted is not erased by this stance; it is, as Gopnik points out, “intensified”. These fragile and broken bodies only increase our visceral response, allowing us, even daring us to stare.

As for me, I steal this, all of it. I want my photographs to catch you in the gut before your brain catches up. Even as I alter my images by hand and push them gently backwards in time (another trick to give them the weight of Evidence), I am grabbing every bit of Belief that I can, if only to say: Go ahead, Look.

Harlequin, 2013. Gum Bichromate with watercolor and gouache. 14″ x 11″

2Michael Fried, Absorption and Theatricality: Painting and Beholder in the Age of Diderot (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.)